NB: This is not specifically about Italians, but Italians certainly participated. And it is definitely medieval, so I figured that was close enough for this time.

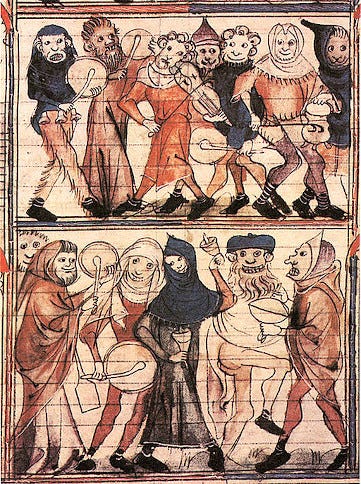

Lowde mynstralcyes. That's what Chaucer calls the huge gathering of minstrels and jongleurs he wrote about in House of Fame. He describes it as a dream sequence, but some musicologists believe Chaucer must have been a witness to one of the annual Lenten minstrel schools that took place in Europe throughout the 14th century and a bit beyond, and which some say began as early as the 12th century.

It's an arresting thought: minstrels, particularly instrumentalists, coming together from many countries to share repertoire, learn new techniques, trade or purchase instruments, recruit new players, and form personal connections. As the fairs became more established, lords or municipalities who employed musicians sent them off to the fairs for career development, because they wanted their musicians to be au courant for the honor, prestige, and pleasure of their masters.

One thing that’s true today was doubtless just as true 700 years ago: when you get a lot of musicians together in one place, interesting things happen.

Terry Jones, the late medievalist and Python, cited an early example:

"... in 1212, when Randulf, Earl of Chester, was besieged by the Welsh in his castle of Rhuddlan in Flintshire. He sent an appeal for help to Roger de Lacy, justiciar and constable of Chester, affectionately known in the local dungeons as 'Roger of Hell.' Roger, casting around for the most effective, vicious and altogether intimidating relief force he could find, realized that Chester was full of jongleurs who had come for the annual fair. He gathered them up and marched them off under his son-in-law Dutton. The Welsh, seeing this fearsome body of determined musicians, singers and prestidigitators bearing down on them ready to launch into an immediate performance of their terrifying arts, fled." (Medieval Lives by Terry Jones)

These early fairgoers were wandering minstrels. No doubt when they wandered to Chester they hoped to perform and earn some money; perhaps they hoped to impress a potential employer, so they could achieve some stability and lead a less hand-to-mouth existence.

But it is very likely that they also intended to use the opportunity to meet with other musicians, teach and learn, master new playing styles and techniques, trade gossip, talk about who might be hiring, and just have a good time with their peers.

By the 14th century (and quite possibly earlier), it was no longer only freelance musicians who sought opportunities to congregate for this valuable information exchange. Annual minstrel schools, held in many different locations, hosted scores of musicians whose travel expenses were paid by their employers, investing in the prestige and honor their musical establishments brought them.

Performers were a mobile lot, traveling considerable distances with surprising frequency. The result was a very cosmopolitan European musical culture. Not that the different nations were without their separate, distinctive styles—learning these other styles was, in fact, a large part of the reason musicians wanted to get together. But the musicians themselves were a polyglot and sophisticated bunch of travelers, the sort who today would be frequent fliers. And this at a time when many people never left the village they were born in.

So. Those schools. Let's look at the what, the where, and the when of them, having already given a bit of thought to the why.

The what: The schools were gatherings of musicians, organized and hosted by musicians, often with financial and other support from the host town, which benefited from the commerce generated by so many visitors, not to mention getting to hear a lot of music. The 14th century schools existed primarily, though not exclusively, to serve the needs of instrumental musicians (at that time, that's what menestral usually meant, with a singer called, for example, a menetrier de bouche to make the distinction). By this time, the role of the all-purpose jongleur was shrinking.

The where: Sometimes more than one school was held in a single year, in two different places, but often the venue appears to have rotated among hosting towns. The Low Countries probably hosted most of them; perhaps they were in a sufficiently central location to make it convenient. Records are spotty and not at all centralized, but schools have been reported in Brussels, Mons, Cambrai, Beauvais, Lyon, Geneva, Bourg-en-Bresse, Malines, Bruges, Paris, Tournai, Lille, Douai, Valenciennes, Namur, and Mechlin.

The city or one of its religious houses might house the visitors, or local musicians might extend their hospitality to their traveling colleagues. In Bruges in 1318, we know that the visiting musicians bunked in an area near the Carmelite convent that even today is known as "Speelmansstrate."

The when: Schools were held during Lent, when the musicians' employers couldn't make much use of their services anyway, typically in the week before Laetere Sunday, the fourth Sunday of Lent. That way the attendees had at least 16 days of travel time to get back home in time for Easter, when their talents might be wanted again at home. Also, Laetere Sunday was a bit of a break from Lenten rigors, and was even sometimes celebrated as a feast day—hence, the musicians might get a chance to perform while in their host city. There may well have been some years when my medieval Italians never got there at all, since to go to schools in France or the Low Countries they had to get across the Alps, not always doable that early in the year. Unless they had a water route available, though travel by sea had its own seasonal challenges.

Some could get home in time for Easter, but the musicians from the court of Aragon, for example, usually made it back home between the middle and the end of May. Some years, the minstrels of John of Aragon spent half the year on the road, getting to the schools and back.

A few cities maintained more-or-less permanent schools (Paris, Bruges). Musicians extending their musical boot camp, or waiting for more auspicious travel conditions, might while away some time at these establishments.

We have records of minstrels attending the schools throughout the 14th century and a little beyond, and around that time the schools apparently ceased to exist, or at least ceased to be a major draw for performers from courts and municipalities. One reason certainly was the rise in musical literacy among performers. The schools served a vital function while people still depended on rote learning and memorization to acquire repertoire, but once it was possible to circulate written music and have the players able to read it, long slogs across Europe were no longer so necessary. A bit like conferencing by Zoom rather than sending your employees off on business trips.

A few specific examples:

The court of Burgundy regularly sent its musicians to the schools. They traveled in a group, and received horses, valets, and 20-50 francs apiece from the Duke for expenses.

In 1366, the school held in Brussels hosted minstrels from Denmark, Navarra, Aragon, Lancaster, Bavaria, and Brunswick.

In 1377-8 the Counts of Savoy sent their minstrels to Bourg-en-Bresse, where the chatelain graciously provided them with fodder for their horses.

In 1377, John of Aragon's minstrels brought home a new shawm player, Jacomi Capeta.

In the only mention I found of a school held in England (town unspecified), Brabantine minstrels Hansen and Henderlijn attended in 1365.

John of Aragon's minstrels were charged, in 1381, with locating a bombarde to purchase that would match their other instruments. They failed to do so.

Three of Edward III's musicians—Merlin the fiddler and bagpipers Barberus and Morlanus—were sent "across the seas, to learn new songs" in 1334 or 1335.

It wasn't always an easy trip. Minstrels were even known to die on the journey, and once in a while somebody would return home only to learn that he'd been replaced during his absence, and must now seek work elsewhere.

As to what these musical gatherings accomplished for the state of music in Europe, there's one intriguing example, which, while not tied specifically to a school, may very well have sprung from one. It is unusually specific about timing, too, calling to mind a quote from David Barber's book, Bach, Beethoven and the Boys: Music History as it Ought to be Taught:

"The Renaissance era ended and the Baroque began on March 25, 1600 at 4 o'clock in the afternoon. No other history of music has the courage to make this statement with such conviction."

Our chronicler is not quite that specific. But Tielman Ehnen von Wolfhagen, in his Limburg Chronicle written around 1360, does tell us this:

"Up to now songs had been sung long, with five or six measures, and the masters are making new songs with three measures. Things changed also with regard to trumpet and shawm playing, and music progressed, and had never been as good as it has now started to become. For he who was known, five or six years ago, as a good shawm player throughout the whole country, is not worth a fly [sometimes translated as 'a hill of beans'] now." (Quoted in an article by William Wegman)

So, something happened in or around 1354-5, right in the middle of the heyday of the minstrel schools, which conceptually changed musical performance, and which resulted in important changes in the quality of shawm and trumpet playing. Do we have any idea what it was? Of course not—we should only be so lucky.

But it sounds a lot like the kind of thing that might have emerged from a minstrel school. And even if that wasn’t the source this time, surely it was the schools that managed to disseminate whatever it was within a half-dozen years—a lightning fast record for spreading this sort of trend in the middle ages.

That’s it for the ides of January. I’ll probably have a shorter post out somewhere around the end of the month, and then a regular newsletter again on the ides of February (the 13th). See you then!

This is so lovely! Thank you, Tinney!